Last summer, my family and I took a road trip to Cincinnati, Ohio. Having never been to Cincy, we chose it for its proximity to the Ark Encounter in Williamstown, KY. However, I learned about the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center as I researched the city. What was a random find became one of the highlights.

Like many Black children, at my daughters’ school there is not a sustained effort to acknowledge and teach Black history as a deeply woven and integral component of American history. I am amazed that in this time when we encourage truth-telling, there are still many who’d rather avoid the history of Blacks in this country. It angers me that in a district where we pay substantial property taxes, my daughters are not fairly, thoughtfully, or comprehensively represented.

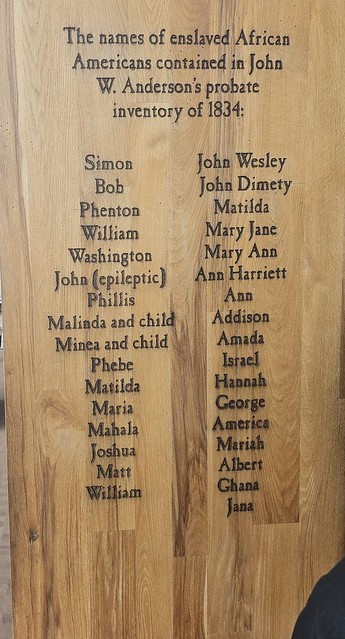

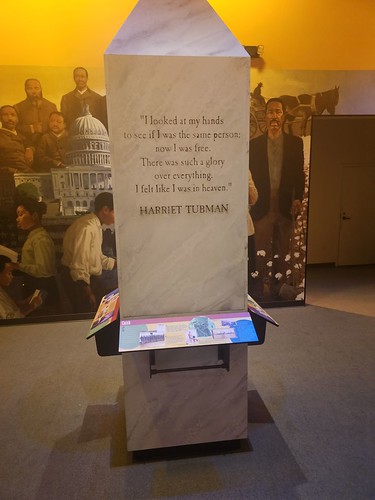

While walking through the Freedom Center, the girls were immersed in the history of their people. They watched a movie about the split-second decision that some enslaved people made to attempt an escape to the freedom that had been stripped from them and made their way through an interactive exhibit that replicated places our people had to hide themselves to evade capture: false wagon bottoms, hidden doors under stairs, and fodder houses. They saw an exhibit entitled, “The Slave Pen,” a structure used by John W. Anderson to temporarily warehouse enslaved people who would be sold farther south. They saw how Mr. Anderson methodically willed his “property” to members of his family as parts of his estate, to ensure that their value would be upheld as his legacy. They asked many questions and took many photos. In between reading and teaching, I wept.

At one point, my youngest, who was ten, tapped me and asked, “Mom, what is that?” I turned to see a picture of a Klansman, mounted on a horse, wielding a burning torch. “Unfortunately,” I said, “hate is a motivator for some.” We talked about Jim Crow and Civil Rights. And I brought the conversation full circle to how that foundation of hate and despair still impacts Blacks in this country. She is a smart, insightful girl and listened intently. She replied, “But I don’t understand why it was allowed. Where were the people that are supposed to help people be treated right by others? Like the police? Or the people who make the laws? Where were they?” Then she paused and said, “But I get it. They didn’t help Breonna Taylor either.”

I wept again.

I vowed then to be more intentional about how my girls learn the history of their people. Black people. Strong-shouldered, proud, resilient, and dogged in our desire to overcome. As much as I want their innocence to remain, I also want them to be informed. I want them to know the stock from which they come, and I want them to know that it is our responsibility to learn. Gone are the days when we allow school districts to dictate what they know and when. This summer, we’ll visit the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Cinaiya Stubbs

Children’s Place Association President & Chief Executive Officer